The Skeleton Coast - a definition of delightful desolation.

We will initially be flying at approximately 10,500 feet but as we approach the Skeleton Coast, we will come down to 'see level' and should reach the camp by 12:30 hours. Heino Jakob, pilot of the single engined 12 seater Cessna Caravan - operated by Sefofane [meaning aeroplane in the Setswana tongue] - that would ferry us over the harsh but dramatic hinterlands of western Namibia, gave us detailed safety instructions and asked us to board. Just four of us to begin with : John Mitten, an experienced guide employed by our hosts Wilderness Safaris, who was to be our chaperone throughout our stay on the Skeleton Coast, then Isaack, an Ovambo lad, returning to his general duties at the camp after leave and finally myself and Brenda, my long suffering wife. Up, up and away as we climbed from Windhoek's centrally situated Eros airport, which caters for light aircraft, course set for Swakopmund. The rolling, pleasantly green swathes of the Khomas Hochland soon give way to the near blinding glare of the Namib Desert, the oldest tract of sand in the world at, according to some sources, eighty million years or so. Much of its remarkable biodiversity is sustained by the advective fog that rolls in from the Atlantic, bringing moisture and sustenance to both flora and fauna in this hyper arid region. And soon we are flying into this murky and moist miasma that usually hangs over the coastal resort of Swakopmund until the sun burns it away by mid morning. Namibians in droves beat a path to the town's doors during holiday periods to escape the hot interior and relax in the misty on shore breezes. We are soon taxiing to the small terminal building to collect two more passengers, Dermot and Helen, a pair of seasoned travellers from the UK who are joining us for the duration. They too are looking forward to exploring the wilderness that awaits us in the far North West.

But first we fly over some of the most dramatic scenery imaginable : Damaraland, the colossal Brandberg mountain, the Messum crater - a relic of volcanic activity measuring a staggering 22 kilometres across - and the extraordinary rock formations of the Ugab area, scintillating mosaics steepling up from the ground, formed following eruptions from the very Earth's core in prehistoric times, when mica, gneiss, granite, and quartz amongst others cooled and compressed to create these simply amazing geological patterns. We pass ephemeral rivers too and then descend gently to the Palmwag airstrip in northern Damaraland. Our final fellow travellers embark here, a Swiss couple from near Bern, Eduard and Claudia, who have flown in from another of Wilderness Safari's prime destinations - Ongava Lodge at the Etosha National Park, one of this continent's premier game parks. So our full camp compliment now settle back to enjoy the last sixty odd minute hop over the Kaokoveld and at much lower level crossing two more ephemeral rivers, the Hoanib and the Hoarusib as they wend their way towards the Atlantic. To our delight and surprise, the latter is running at a pace, this is a rare occurrence indeed. Heino, busy at the controls to afford us all the best possible view, tells us that this will create problems for light aircraft traffic serving the camp: the airstrip for smaller six-seated planes is on the far side of the Hoarusib and with the river in full flow, even the trusty Land Rovers used here by Wilderness will not be able to cross. Therefore planes, in these circumstances, can only use the larger airstrip much nearer the camp, but it's make up of soft sand precludes the slighter aircraft from trying to land: an attempt long ago ended with propeller in the sand, the plane tending to the upright ! So the , pilot will be asked to do some shuttle work later in his larger Caravan and collect any passengers earmarked to travel from elsewhere in the 'six-seaters' and land them at the camp runway : desert logistics to the fore.

Swinging out to sea past the mouth of the river, we can clearly the silt carried down in the flow being pulled north by the cold Benguela current which hugs this western coastline. A ribbon of brown staining the blue white flecked ocean as far as the eye can see from our aerial viewpoint. The Benguela current's cold water is responsible for the formation of the life giving advective fogs so important to the character of the Skeleton Coast and adjoining Namib Desert: the air travelling over the warmer waters further offshore, with it's inherently higher evaporation rate, meets the cooler air above this chillier current, these two air masses then rising where they meet the elevation of the land and thus the fog is formed. We turn inland and make our landing approach, spotting two lonely Oryx isolated in this panorama of wilderness.

"Welcome to Skeleton Coast Camp, we hope you had a pleasant flight and that you will enjoy your stay with us here." Andi [Andrea Staltmeier], the resident manager of the camp - albeit in a relief role whilst the normal incumbents are away on leave -

greets us all individually and then invites us to climb into the two Land Rover Defenders parked nearby, for the short transfer to our home for the next few days. We are booked onto a five day, four night trip commencing Saturday and returning us to Windhoek the following Wednesday. The schedules also allow for a shorter arrive Wednesday, depart Saturday routine including obviously three nights at the coastal base. More recently introduced is a longer seven night visit taking in the whole week.

From the sandy airstrip, hardly recognisable as such save for stones neatly laid to mark the perimeter and a solitary windsock, we ride down into the dry Khumib river and wend our way to the main area of the camp. We can see six chalets, wooden framed tented constructions, randomly located in the river bed, but raised on stilts just in case the river should run. These elevated positions were deemed necessary after one of the original chalets was washed away when this ephemeral river ran copiously to literally greet the camps opening in April 2000! We are soon shown to our chalets and invited to walk back to the central building, raised off the ground in similar fashion, for a welcoming drink and buffet lunch. This complex comprises a spacious open plan lounge, bar and dining area together with the kitchen and such paraphernalia necessary to feed the masses. Our flight companion Isaack is immediately pressed into service as barman and head waiter.

After lunch, siesta time, and guide John asks us to assemble later in the afternoon when our explorations will begin in earnest. Rooms are comfortable enough, rustically furnished with en suite facilities. Water is in very short supply in this arid area and it is necessary to make a 90 km round trip with a tractor to collect water from the nearest borehole as often as demand requires. Terms of the concession held by our hosts prevents them from sinking a borehole nearer the camp.

As elsewhere in Namibia, we are reminded to be frugal in our usage of the precious H2O. So later it's tea, coffee and home made rusks - legendary in these parts - and then we climb into the Land Rover for our first drive out. There are two Defenders at the camp, both very heavily modified 110 models with specially extended chassis, now some four years old. Our transport will seat eleven, eight inside in three rows whilst three can perch on top of the roof section accessing those grandstand seats through the enormous hatch which, when raised, affords the passengers inside wonderful uninterrupted viewing and consequent camera opportunities from a standing position. Very cleverly designed, but with a large amount of steel in this makeover replacing Land Rover's much vaunted and virtually everlasting aluminium panels, maybe the ozone from the Atlantic will wreak some havoc in time. But meantime, there's a wheel in each corner [more of those later] and with the trusty 2.5 litre 300 Tdi Gem power plant under the bonnet, we thus set off down the Khumib river bed. Today's excursion is in reality a getting to know each other trip and we head for the locally named "Rock Garden" only a few kilometres from camp. Impressive rock formations soon surround us after we drive out from the dry water course, and we spend an hour or so on foot exploring the surroundings noting the variety of shrubs, succulents and plant life surviving in these harsh conditions by dint of dew and the advective coastal fog, as well as either spotting a few desert dwelling insects, reptiles and small mammals or seeing signs of their existence by dint of tracks or entrances to burrows and hideaways. Brenda and I had seen a small sand snake on leaving our chalet earlier, but we were not to spot any others for the length of our sojourn. Upon congregating back at our transport, guide John had transformed the desert into a miniature watering hole, sundowners for all. On our return to camp, we enjoyed the first of many fine meals to be prepared by our hosts, a standard well maintained considering the complicated logistics involved at such a remote destination. Coffee and then some sleep, for John suggested reveille at 06:00 the following morning.

Day two is just dawning as piping hot water is delivered to our door: rooibos tea and a pleasant shower, solar powered like the other energy sources utilised in all the accommodation, followed by a brief buffet breakfast sets us up for the day's explorations. And today we will take in so much, bearings set for the coastline itself.

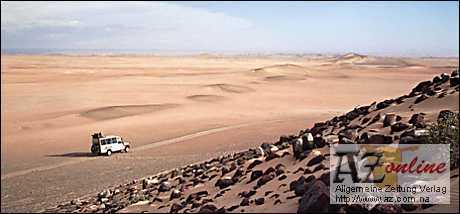

Wilderness Safaris are at pains to ensure that their Land Rovers stick to existing tracks, in the knowledge that a single vehicle's fresh tracks across the gravel plains prevalent in this area might still be visible up to a century later. Some distance from base, in a water course scattered with one or two trees - a fairly rare sight in this section of the Skeleton Coast Park - we spot a pale chanting goshawk and also realise we are being tracked by one of the ubiquitous pied crows living in the area. Grazing, and more so seemingly relatively untroubled by our mechanical intrusion, is a group of springbok pleasantly silhouetted against the desert background. We soon enter a dune field arising from the gravel plains, captivating crescents of barchan dunes formed by the prevailing south west winds. These dunes move visibly, anything between 2 up to as much as 15 metres a year, this shift being caused by the wind picking up grains of sand from the dune's back slope and depositing them on the front face. The dunes invariably travel north east, the direction in which their formation always points.

The Defender crests one of the bigger dunes, affording us a wonderful vista towards the Atlantic with the plains between the dunes and the briny interrupted by a rift of dark basaltic rock. Here on the dune we quickly spot a tok-tokkie, a tenebrionid beetle which has developed a fascinating method of obtaining water. They climb to the crest of a dune in the early morning and turn towards the wind, letting the fog condense on their bodies. Then by literally doing a headstand, using their rear legs as support, they let the droplets run down their back and into a channel towards their mouths allowing them to drink the water they need. Other beetles of this family are coloured white and yellow, research proving that their body temperatures are reduced by up to five degrees Celsius, another useful desert adaptation.

Leaving the dune area behind us we next come across a brackish spring providing wildlife with much needed water in this arid environment. No game can we see, but the birders amongst us have seen red billed francolin, ludwigs bustard and ruppells korhaan in the vicinity. The boggy area around the spring is quicksand indeed and some more intrepid visitors are quickly sinking to their knees, contorting their bodies easily with the sand gripping their legs. All in good fun, but the real danger of unknowingly being trapped in such mire is very apparent to everyone. Nature has a multitude of fierce defences.

And suddenly we are at the shore, the sea roaring in perpetual motion. Eerie, the absolute desolation, the mist rolling furiously in from afar, the debris of nature lying untouched on the sand. The human brain is hard put to assimilate such a scene, to soak up the sound of silence, to understand a place where nothing is everything. We wander on virgin sand, taking in this stunning solitude. But reality will now unkindly re-assert itself: the Land Rover has a flat tyre. Yours truly, long associated with this flagship breed of 4x4, assists our trusty driver/guide in a swift wheel change [two spares are carried] and our vehicle now strides along the coastline, water almost lapping at it's wheels. We see jackal, an occasional seal pup, a lot of whalebones washed ashore from the whaling ships of days gone by, myriads of ghost crabs marching in their sideways style, we watch damara terns, sanderlings and many gulls and we encounter lots more mist and spray. The air is bracing and cool, a welcome relief from the relentless heat of the Namibian interior.

To Cape Frio then, first to sit in canvas comfort and enjoy an excellent al fresco lunch, and then to study at close quarters the tens of thousands of seals that congregate in the Cape Frio environs to both rest after feeding plentifully in the food rich northern coastal waters and then to find a breeding mate whilst still in prime physical condition. The strongest will hold a beach territory closest to the water, and thus the weaker brethren who must set their stall further into the sand mass will always have an adventurous journey back into the water, running the gauntlet indeed of their more powerful kin. Males bark fiercely, tussle and joust for position and spouse, their mates and offspring joining in this cacophony of sound, notwithstanding the pungent ammonia like smells that fill the air. Triple banded and chestnut banded plovers hop around nearby. From here, we turn inland for the long journey back to the camp. We will cover over 200 kilometres during the day. Climbing away from the shore we now enter yet another completely different environment, skirting first the enormous Cape Frio saltpan, which stretches for some ninety kilometres along the coast, at some points several kms wide. The dark hues of the pan change to a brilliant white after any rare rain, whilst the perfectly plausible production of salt is rendered a non starter by way of the excessive transport costs that would be entailed.

We then are back amongst the rocks, the Agate Mountain to be precise, its shadowy outlines contrasting with the following reddish feldspar gravel plains and more sandy stretches punctuated with shrub coppice dunes, formed where wind blown sand has built up around vegetation. Magnetite, a form of iron ore, adds striped patterns of black to these sandy humps. In all a veritable cornucopia of colour.

Wending our way through the plains, we come across a rare group of Oryx - including calves - grazing gracefully on the minimal vegetation available. Then, bang, another puncture. And worse is to come : John goes to retrieve the high lift from its secured resting place above the front bumper, only to find that maybe it was not secured, it's gone! It must have fallen off twixt the beach and here. So three wheels on our wagon, and no jack, no brownie points for the driver. But desert ingenuity reigns and soon we have the Land Rover's axles supported by towers of rocks, its wheels well chocked. Then out with the shovel, dig a large pit under the flat tyre, and hey presto, the tyre is removed whilst the stone jacks hold the vehicle upright. These regular flats are probably caused by impurities such as rust on the inner surface of the wheel rim and the heat generated by the inner tube running at the low pressure required to give the tyre adhesion on these rough, natural surfaces combining to perforate the tube or to dislodge a previously glued repair patch. New wheels, maybe tubeless tyres but certainly a solution would be nice. So job done, but not yet the journey.

Our last stop finds us being quizzed as to the consequence of the pattern of a series of stone circles we discover protruding from the ground. Not the more normal and obvious small stone dwellings built by Damara and Herrero locals whilst tending their small stock in more recent times, these primitive slab areas maybe are much, much older. A relic from the days of the earliest hunter / gatherers perhaps, the beach dwelling strandlopers ? These guys eked out an existence similar to the brown hyenas still living on the shoreline today. Now archaeologists have confirmed that these stone circles in the Park are not burial sites as was first mooted. One piece of conjecture, given their position in a narrowing triangle of ground edged by higher ridges is that they were hunting hides, allowing the strandlopers to pounce on game that was driven towards them by others. Another that they were the base stones for some form of primitive accommodation. Our heads full of possibilities, we are soon back at camp, enjoying a nice supper and a sound sleep. A memorable day.

The dawn beckoned bright and beautiful with the line of fog visible towards the coast. John and Defender await us, tyres retubed and tanks refilled. This remotest of tourist outposts is very much self sufficient, for once supplies are brought in overland the infrastructure and staff here are set up to handle all requirements. The Land Rovers are serviced at night, the picnic lunches made up long before dawn, logistics rule ok.

Today finds us meandering towards the ephemeral Hoarusib river, in full flow remember, and that is a stunning sight [and of course fabulous life bringer to all things in nature] which might only happen once annually, or in a really good rainy season maybe several times. First, we pause at the lichen fields on the gravels plains we are traversing. Lichen depend and survive, like all other desert vegetation here on the Skeleton Coast, through moisture brought in by the advective fogs rolling in from the sea. Fields of dark, blackened lichen will amazingly turn into banks of bright orange or lush green once this dampness is upon them. Technically the lichen are not plants, rather micro organisms composed of algae and fungi which complement each other. The algae provide the food cycle, the fungi shelter, plant form and germination. Lichen can survive, like the Oryx and much else around them, for long periods without water. Other fascinating plants growing here in the desert are the bushman's candle, noted for both its pretty pink flowers and it's moisture retaining bark, which when dried out and burned, gives out both a candle type light and a incense like aroma. The welwitschia mirabilis is the well documented wonder plant, growing only here in the Namib. Although it can reach a height of up to two metres, with the largest specimens having a diameter of well over half that, the welwitschia only ever produces two leaves. These in turn can be scorched almost black by the sun but have millions of cells, on both their top and bottom sides, which absorb moisture and allow it to survive. The plants may look ungainly and shrivelled, but they are reckoned to be one of the oldest plants known to man, their long lived ancestry continued by wind pollination between the separate male and female plants.

Driving towards the river, our walking, talking compendium of knowledge, John, invites us to stroll with him to take a close look at the fascinating 'clay castles' in the nearby Hoarusib canyon. Ancient river silts, built up over thousands, possibly millions of years, have gradually been eroded by both wind and water to form these extraordinary castles clinging to the sides of the canyon. The erosion has even shaped pillars which add a dimensional effect to the facefront of these dramatic formations. Yet another stunning landscape to add to the memory banks.

Between here and the river itself we negotiate a huge dune slope careering down towards the water course. John is extremely vigilant on arrival at the thick lush vegetation on the banks of the Hoarusib to ensure that we will not be in the company of any lions that might be resting in the cool shady undergrowth. No sign is seen of the big cats although there is much evidence of elephants having been in the area. But with the river running, we are very unlikely to spot any today. However when the river bed is dry, a highlight of any holiday here would be tracking and discovering these remarkable desert adapted mammals. The swirling waters will do for us though.

And wading into the torrents is exactly where we go, taking great care to avoid any deep holes in the river bed scoured out by the fast flowing water. The very sight of this full river in its desert environment is stunning, a life blood running in front of our very eyes. We dry off, not difficult under this blazing sun, and picnic. No time for siestas, John suggests, as we head for the river mouth, where this gurgling mass is lost to the ocean forever. Backtracking up that immense dune slope gets the adrenalin flowing and then we move back inland before turning once more for the coast. Again we encounter marvellous dune scenery [photo shoots all round] before we drop down to sea level. The water course is, if anything, more challenging here and we spot the first people we have seen in three days on the other bank, along with four bakkies. Conference is finally held almost in mid river; John Patterson, head of Nature Conservation in these parts, is escorting a French film crew shooting a 35mm film of the astonishing landscapes along the Skeleton Coast, through the Park. They are holed up as such, waiting for the water levels to drop and afford safe transit across. Should the scenario continue much longer, then they will turn and retreat, bowing to Mother Nature.

This whole proclaimed National Park is off limits to the public, the only access being either by permit obtained through the Ministry of Environment and Tourism [MET] or by holidaying with Wilderness Safaris, as we are, they being the sole concession holders for tourist activities in the Park. Wildnerness themselves are closely monitored by the MET but the company's attitude to tourism is both responsible and eco friendly and they are proud to be considered at this stage good guardians of these wilds. A definition of wilderness - as applicable in South Africa, who have already designated various areas of the Republic as "Wilderness Areas", these being protected in the country's legislation - is therefore perhaps relevant to us during our stay at the coast. "Such an area is defined as uninhabited, having no lasting human structures, being large enough to give a feeling of solitude, have all human activities concealed from sight or hearing and not be 'managed' in any way." Well, you sense that here you are as close as you can get in Namibia to those designations; nature is all around you, in the main unspoilt and untrammelled. You feel quite privileged to be here.

We drive on, once more hugging the seashore and head towards Rocky Point. Here we encounter a grim reminder of why this coastline is so named. In the surf lies the easily discernible wreck of the tugboat 'Sir Charles Elliott' which was carried way off course by strong currents and stranded close to the shore back in 1942. The vessel was on it's way to assist in the rescue of the British cargo liner 'The Dunedin Star' which had run aground further to the north, with over 100 people and much cargo on board. The story is wonderfully recreated in John Marsh's book 'The Skeleton Coast', a riveting tale of an astonishing rescue. In despairing efforts to save their crew mates, several members of the tugboat, which still rests here to this day, tried to swim ashore. The first mate was lost and never seen again, whilst one other crew member, Mathias Koraseb did reach the shore but then died of exhaustion. He is buried on the spot where we stand today, with a tombstone commemorating both his body and the lost first mate. They call it 'the loneliest grave in the world'. Our passage home is only interrupted by another flat tyre. Dinner tonight is taken under a giant old lead wood tree that stands proudly next to the raised decking of the lounge boma. A panoply of myriad stars in a clear African sky is almost food enough itself. And so to bed.

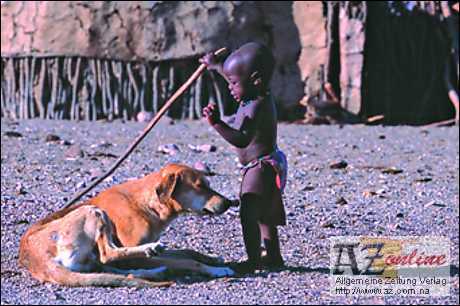

We begin our fourth day, after our usual wake up routine, by tracking down the Khumib River and actually leaving the concession area. Guide John wants to take us to a traditional Himba village, where the natives' lives perhaps continue closer to the format necessarily followed in days of yore than in any other part of Namibia. En route, a female Himba flags us down in the riverbed. She is wife of the chief's brother who, with her children, is living and tending their goats in an area where some showers have produced reasonable grazing, but many kilometres from the village. She begs a lift, the pungent aroma of her traditional skin covering - a mixture of red ochre and animal fat - soon filling the Defender. Her mission to get water for her dwelling, saving her a long trek by donkey. We reach the village running with one flat tyre, already the second of the day, so John - after introducing us to the village inhabitants - attends to the necessary. The centre of the village features a kraal of poles hewn locally in which the Himba dead are buried. An ancestral fire burns a few metres from the entrance. It would cause huge offence if a non tribal member were to walk between said fire and the entrance. That tract is sacred to the Himbas. Then, several women disappear into their pole based huts, which are plastered with a mixture of mud and cattle dung to keep the interiors cool and sheltered from the wind. They reappear carrying large sacks containing a huge variety of bracelets, necklaces, wood carvings and water carriers and dishes tightly woven from local vegetation. At once, the goods are displayed on mats and the area takes on the mantle of a craft market. Incongruous perhaps in these simple surroundings, but the tribes people need to make an income for themselves. One hopes that they are not too reliant on this weekly pilgrimage by our hosts. We leave for lunch at the camp, spotting a large group of Oryx in the veldt and coming across a total of seven lappet faced vultures on this single journey. During our divers travels we also had seen martial and black chested snake eagles, and also a huge spotted eagle owl. More surprisingly, near the camp we find two guys walking through the undergrowth. It turns out their vehicle has broken a drive shaft on the only local road running just outside the concession area, and one of the pair - knowing of the Skeleton Coast Camp - decided it would be best to 'trespass' into the camp area and seek help. Radio contact with the outside world would then be possible. So their long hot journey was eased by a lift. Lucky for some.

We have the opportunity to siesta briefly before our second excursion of the day. We drive out into the gravel plains and then climb up a koppie that gives us a breathtaking view of our surroundings: gravel plains, dunes, mountains - is this the best so far, a perfect snapshot of the Park, a kaleidoscope of colour, a barren but hauntingly beautiful landscape. The Skeleton Coast in one. We then indulge in solitaire, a time spent entirely on our own, each with their own thoughts, each witnessing at once the splendour and the silence. Thirty minutes well spent, refreshing the very soul.

And so to the last supper, asparagus salad, game and veggies, chocolate mousse cake and coffee. All our food delicious, with wine and cool drinks to complement same readily available. Then a surprise for even the management: the kitchen doors burst open and the full complement of staff treat us to an impromptu concert. Yolanda, Yvonne, Margaret, Isaack, Theo and Janneman - was this the Skeleton Coast Choir?

This mixture of Himba, Herero and Ovambo combined in perfect harmony, and thrilled us all. They gave us traditional songs and even indulged in theatre, portraying the very acts the songs described. During their lion hunt routine audience participation was mandatory, oh what fun.

And now, the end is near. But time still for one last escape into the great outdoors. With Land Rover we travel to near the coastline and visit a small amethyst mining operation run by a Swakopmund based enterprise who has bought a concession from the Government. Earlier in the week we had seen instances of very low key diamond prospecting concessions based much closer to the shore, although contrary to popular opinion no great tracts of diamonds in large enough quantities to warrant commercial operations have ever been found on this northern stretch of the Namib coastline. When mining for amethysts the concession holders use jack hammers to split open the geodes they uncover, revealing almost like the centre of an egg, the purple, valuable gemstones. What a wonderful place to set up your small business enterprise.

We return to camp for a last chat with Andi, a glass of Dutch courage for those who want it and say our good byes to all the staff and in particular John, our valiant guide, his biceps rippling after all those wheel changes. We won't forget John urging us to link arms and slide down the steep, steep slip face of a roaring dune. And roar it did.

But the only howl now was that of the little Cessna lifting us into the sky, and taking us back whence we came. Most of all, these memories will remain with us all for a long, long time. What else can you say about one of the last remaining wilderness areas on the planet Earth.

More Information about this trip: www.wilderness-safaris.com

But first we fly over some of the most dramatic scenery imaginable : Damaraland, the colossal Brandberg mountain, the Messum crater - a relic of volcanic activity measuring a staggering 22 kilometres across - and the extraordinary rock formations of the Ugab area, scintillating mosaics steepling up from the ground, formed following eruptions from the very Earth's core in prehistoric times, when mica, gneiss, granite, and quartz amongst others cooled and compressed to create these simply amazing geological patterns. We pass ephemeral rivers too and then descend gently to the Palmwag airstrip in northern Damaraland. Our final fellow travellers embark here, a Swiss couple from near Bern, Eduard and Claudia, who have flown in from another of Wilderness Safari's prime destinations - Ongava Lodge at the Etosha National Park, one of this continent's premier game parks. So our full camp compliment now settle back to enjoy the last sixty odd minute hop over the Kaokoveld and at much lower level crossing two more ephemeral rivers, the Hoanib and the Hoarusib as they wend their way towards the Atlantic. To our delight and surprise, the latter is running at a pace, this is a rare occurrence indeed. Heino, busy at the controls to afford us all the best possible view, tells us that this will create problems for light aircraft traffic serving the camp: the airstrip for smaller six-seated planes is on the far side of the Hoarusib and with the river in full flow, even the trusty Land Rovers used here by Wilderness will not be able to cross. Therefore planes, in these circumstances, can only use the larger airstrip much nearer the camp, but it's make up of soft sand precludes the slighter aircraft from trying to land: an attempt long ago ended with propeller in the sand, the plane tending to the upright ! So the , pilot will be asked to do some shuttle work later in his larger Caravan and collect any passengers earmarked to travel from elsewhere in the 'six-seaters' and land them at the camp runway : desert logistics to the fore.

Swinging out to sea past the mouth of the river, we can clearly the silt carried down in the flow being pulled north by the cold Benguela current which hugs this western coastline. A ribbon of brown staining the blue white flecked ocean as far as the eye can see from our aerial viewpoint. The Benguela current's cold water is responsible for the formation of the life giving advective fogs so important to the character of the Skeleton Coast and adjoining Namib Desert: the air travelling over the warmer waters further offshore, with it's inherently higher evaporation rate, meets the cooler air above this chillier current, these two air masses then rising where they meet the elevation of the land and thus the fog is formed. We turn inland and make our landing approach, spotting two lonely Oryx isolated in this panorama of wilderness.

"Welcome to Skeleton Coast Camp, we hope you had a pleasant flight and that you will enjoy your stay with us here." Andi [Andrea Staltmeier], the resident manager of the camp - albeit in a relief role whilst the normal incumbents are away on leave -

greets us all individually and then invites us to climb into the two Land Rover Defenders parked nearby, for the short transfer to our home for the next few days. We are booked onto a five day, four night trip commencing Saturday and returning us to Windhoek the following Wednesday. The schedules also allow for a shorter arrive Wednesday, depart Saturday routine including obviously three nights at the coastal base. More recently introduced is a longer seven night visit taking in the whole week.

From the sandy airstrip, hardly recognisable as such save for stones neatly laid to mark the perimeter and a solitary windsock, we ride down into the dry Khumib river and wend our way to the main area of the camp. We can see six chalets, wooden framed tented constructions, randomly located in the river bed, but raised on stilts just in case the river should run. These elevated positions were deemed necessary after one of the original chalets was washed away when this ephemeral river ran copiously to literally greet the camps opening in April 2000! We are soon shown to our chalets and invited to walk back to the central building, raised off the ground in similar fashion, for a welcoming drink and buffet lunch. This complex comprises a spacious open plan lounge, bar and dining area together with the kitchen and such paraphernalia necessary to feed the masses. Our flight companion Isaack is immediately pressed into service as barman and head waiter.

After lunch, siesta time, and guide John asks us to assemble later in the afternoon when our explorations will begin in earnest. Rooms are comfortable enough, rustically furnished with en suite facilities. Water is in very short supply in this arid area and it is necessary to make a 90 km round trip with a tractor to collect water from the nearest borehole as often as demand requires. Terms of the concession held by our hosts prevents them from sinking a borehole nearer the camp.

As elsewhere in Namibia, we are reminded to be frugal in our usage of the precious H2O. So later it's tea, coffee and home made rusks - legendary in these parts - and then we climb into the Land Rover for our first drive out. There are two Defenders at the camp, both very heavily modified 110 models with specially extended chassis, now some four years old. Our transport will seat eleven, eight inside in three rows whilst three can perch on top of the roof section accessing those grandstand seats through the enormous hatch which, when raised, affords the passengers inside wonderful uninterrupted viewing and consequent camera opportunities from a standing position. Very cleverly designed, but with a large amount of steel in this makeover replacing Land Rover's much vaunted and virtually everlasting aluminium panels, maybe the ozone from the Atlantic will wreak some havoc in time. But meantime, there's a wheel in each corner [more of those later] and with the trusty 2.5 litre 300 Tdi Gem power plant under the bonnet, we thus set off down the Khumib river bed. Today's excursion is in reality a getting to know each other trip and we head for the locally named "Rock Garden" only a few kilometres from camp. Impressive rock formations soon surround us after we drive out from the dry water course, and we spend an hour or so on foot exploring the surroundings noting the variety of shrubs, succulents and plant life surviving in these harsh conditions by dint of dew and the advective coastal fog, as well as either spotting a few desert dwelling insects, reptiles and small mammals or seeing signs of their existence by dint of tracks or entrances to burrows and hideaways. Brenda and I had seen a small sand snake on leaving our chalet earlier, but we were not to spot any others for the length of our sojourn. Upon congregating back at our transport, guide John had transformed the desert into a miniature watering hole, sundowners for all. On our return to camp, we enjoyed the first of many fine meals to be prepared by our hosts, a standard well maintained considering the complicated logistics involved at such a remote destination. Coffee and then some sleep, for John suggested reveille at 06:00 the following morning.

Day two is just dawning as piping hot water is delivered to our door: rooibos tea and a pleasant shower, solar powered like the other energy sources utilised in all the accommodation, followed by a brief buffet breakfast sets us up for the day's explorations. And today we will take in so much, bearings set for the coastline itself.

Wilderness Safaris are at pains to ensure that their Land Rovers stick to existing tracks, in the knowledge that a single vehicle's fresh tracks across the gravel plains prevalent in this area might still be visible up to a century later. Some distance from base, in a water course scattered with one or two trees - a fairly rare sight in this section of the Skeleton Coast Park - we spot a pale chanting goshawk and also realise we are being tracked by one of the ubiquitous pied crows living in the area. Grazing, and more so seemingly relatively untroubled by our mechanical intrusion, is a group of springbok pleasantly silhouetted against the desert background. We soon enter a dune field arising from the gravel plains, captivating crescents of barchan dunes formed by the prevailing south west winds. These dunes move visibly, anything between 2 up to as much as 15 metres a year, this shift being caused by the wind picking up grains of sand from the dune's back slope and depositing them on the front face. The dunes invariably travel north east, the direction in which their formation always points.

The Defender crests one of the bigger dunes, affording us a wonderful vista towards the Atlantic with the plains between the dunes and the briny interrupted by a rift of dark basaltic rock. Here on the dune we quickly spot a tok-tokkie, a tenebrionid beetle which has developed a fascinating method of obtaining water. They climb to the crest of a dune in the early morning and turn towards the wind, letting the fog condense on their bodies. Then by literally doing a headstand, using their rear legs as support, they let the droplets run down their back and into a channel towards their mouths allowing them to drink the water they need. Other beetles of this family are coloured white and yellow, research proving that their body temperatures are reduced by up to five degrees Celsius, another useful desert adaptation.

Leaving the dune area behind us we next come across a brackish spring providing wildlife with much needed water in this arid environment. No game can we see, but the birders amongst us have seen red billed francolin, ludwigs bustard and ruppells korhaan in the vicinity. The boggy area around the spring is quicksand indeed and some more intrepid visitors are quickly sinking to their knees, contorting their bodies easily with the sand gripping their legs. All in good fun, but the real danger of unknowingly being trapped in such mire is very apparent to everyone. Nature has a multitude of fierce defences.

And suddenly we are at the shore, the sea roaring in perpetual motion. Eerie, the absolute desolation, the mist rolling furiously in from afar, the debris of nature lying untouched on the sand. The human brain is hard put to assimilate such a scene, to soak up the sound of silence, to understand a place where nothing is everything. We wander on virgin sand, taking in this stunning solitude. But reality will now unkindly re-assert itself: the Land Rover has a flat tyre. Yours truly, long associated with this flagship breed of 4x4, assists our trusty driver/guide in a swift wheel change [two spares are carried] and our vehicle now strides along the coastline, water almost lapping at it's wheels. We see jackal, an occasional seal pup, a lot of whalebones washed ashore from the whaling ships of days gone by, myriads of ghost crabs marching in their sideways style, we watch damara terns, sanderlings and many gulls and we encounter lots more mist and spray. The air is bracing and cool, a welcome relief from the relentless heat of the Namibian interior.

To Cape Frio then, first to sit in canvas comfort and enjoy an excellent al fresco lunch, and then to study at close quarters the tens of thousands of seals that congregate in the Cape Frio environs to both rest after feeding plentifully in the food rich northern coastal waters and then to find a breeding mate whilst still in prime physical condition. The strongest will hold a beach territory closest to the water, and thus the weaker brethren who must set their stall further into the sand mass will always have an adventurous journey back into the water, running the gauntlet indeed of their more powerful kin. Males bark fiercely, tussle and joust for position and spouse, their mates and offspring joining in this cacophony of sound, notwithstanding the pungent ammonia like smells that fill the air. Triple banded and chestnut banded plovers hop around nearby. From here, we turn inland for the long journey back to the camp. We will cover over 200 kilometres during the day. Climbing away from the shore we now enter yet another completely different environment, skirting first the enormous Cape Frio saltpan, which stretches for some ninety kilometres along the coast, at some points several kms wide. The dark hues of the pan change to a brilliant white after any rare rain, whilst the perfectly plausible production of salt is rendered a non starter by way of the excessive transport costs that would be entailed.

We then are back amongst the rocks, the Agate Mountain to be precise, its shadowy outlines contrasting with the following reddish feldspar gravel plains and more sandy stretches punctuated with shrub coppice dunes, formed where wind blown sand has built up around vegetation. Magnetite, a form of iron ore, adds striped patterns of black to these sandy humps. In all a veritable cornucopia of colour.

Wending our way through the plains, we come across a rare group of Oryx - including calves - grazing gracefully on the minimal vegetation available. Then, bang, another puncture. And worse is to come : John goes to retrieve the high lift from its secured resting place above the front bumper, only to find that maybe it was not secured, it's gone! It must have fallen off twixt the beach and here. So three wheels on our wagon, and no jack, no brownie points for the driver. But desert ingenuity reigns and soon we have the Land Rover's axles supported by towers of rocks, its wheels well chocked. Then out with the shovel, dig a large pit under the flat tyre, and hey presto, the tyre is removed whilst the stone jacks hold the vehicle upright. These regular flats are probably caused by impurities such as rust on the inner surface of the wheel rim and the heat generated by the inner tube running at the low pressure required to give the tyre adhesion on these rough, natural surfaces combining to perforate the tube or to dislodge a previously glued repair patch. New wheels, maybe tubeless tyres but certainly a solution would be nice. So job done, but not yet the journey.

Our last stop finds us being quizzed as to the consequence of the pattern of a series of stone circles we discover protruding from the ground. Not the more normal and obvious small stone dwellings built by Damara and Herrero locals whilst tending their small stock in more recent times, these primitive slab areas maybe are much, much older. A relic from the days of the earliest hunter / gatherers perhaps, the beach dwelling strandlopers ? These guys eked out an existence similar to the brown hyenas still living on the shoreline today. Now archaeologists have confirmed that these stone circles in the Park are not burial sites as was first mooted. One piece of conjecture, given their position in a narrowing triangle of ground edged by higher ridges is that they were hunting hides, allowing the strandlopers to pounce on game that was driven towards them by others. Another that they were the base stones for some form of primitive accommodation. Our heads full of possibilities, we are soon back at camp, enjoying a nice supper and a sound sleep. A memorable day.

The dawn beckoned bright and beautiful with the line of fog visible towards the coast. John and Defender await us, tyres retubed and tanks refilled. This remotest of tourist outposts is very much self sufficient, for once supplies are brought in overland the infrastructure and staff here are set up to handle all requirements. The Land Rovers are serviced at night, the picnic lunches made up long before dawn, logistics rule ok.

Today finds us meandering towards the ephemeral Hoarusib river, in full flow remember, and that is a stunning sight [and of course fabulous life bringer to all things in nature] which might only happen once annually, or in a really good rainy season maybe several times. First, we pause at the lichen fields on the gravels plains we are traversing. Lichen depend and survive, like all other desert vegetation here on the Skeleton Coast, through moisture brought in by the advective fogs rolling in from the sea. Fields of dark, blackened lichen will amazingly turn into banks of bright orange or lush green once this dampness is upon them. Technically the lichen are not plants, rather micro organisms composed of algae and fungi which complement each other. The algae provide the food cycle, the fungi shelter, plant form and germination. Lichen can survive, like the Oryx and much else around them, for long periods without water. Other fascinating plants growing here in the desert are the bushman's candle, noted for both its pretty pink flowers and it's moisture retaining bark, which when dried out and burned, gives out both a candle type light and a incense like aroma. The welwitschia mirabilis is the well documented wonder plant, growing only here in the Namib. Although it can reach a height of up to two metres, with the largest specimens having a diameter of well over half that, the welwitschia only ever produces two leaves. These in turn can be scorched almost black by the sun but have millions of cells, on both their top and bottom sides, which absorb moisture and allow it to survive. The plants may look ungainly and shrivelled, but they are reckoned to be one of the oldest plants known to man, their long lived ancestry continued by wind pollination between the separate male and female plants.

Driving towards the river, our walking, talking compendium of knowledge, John, invites us to stroll with him to take a close look at the fascinating 'clay castles' in the nearby Hoarusib canyon. Ancient river silts, built up over thousands, possibly millions of years, have gradually been eroded by both wind and water to form these extraordinary castles clinging to the sides of the canyon. The erosion has even shaped pillars which add a dimensional effect to the facefront of these dramatic formations. Yet another stunning landscape to add to the memory banks.

Between here and the river itself we negotiate a huge dune slope careering down towards the water course. John is extremely vigilant on arrival at the thick lush vegetation on the banks of the Hoarusib to ensure that we will not be in the company of any lions that might be resting in the cool shady undergrowth. No sign is seen of the big cats although there is much evidence of elephants having been in the area. But with the river running, we are very unlikely to spot any today. However when the river bed is dry, a highlight of any holiday here would be tracking and discovering these remarkable desert adapted mammals. The swirling waters will do for us though.

And wading into the torrents is exactly where we go, taking great care to avoid any deep holes in the river bed scoured out by the fast flowing water. The very sight of this full river in its desert environment is stunning, a life blood running in front of our very eyes. We dry off, not difficult under this blazing sun, and picnic. No time for siestas, John suggests, as we head for the river mouth, where this gurgling mass is lost to the ocean forever. Backtracking up that immense dune slope gets the adrenalin flowing and then we move back inland before turning once more for the coast. Again we encounter marvellous dune scenery [photo shoots all round] before we drop down to sea level. The water course is, if anything, more challenging here and we spot the first people we have seen in three days on the other bank, along with four bakkies. Conference is finally held almost in mid river; John Patterson, head of Nature Conservation in these parts, is escorting a French film crew shooting a 35mm film of the astonishing landscapes along the Skeleton Coast, through the Park. They are holed up as such, waiting for the water levels to drop and afford safe transit across. Should the scenario continue much longer, then they will turn and retreat, bowing to Mother Nature.

This whole proclaimed National Park is off limits to the public, the only access being either by permit obtained through the Ministry of Environment and Tourism [MET] or by holidaying with Wilderness Safaris, as we are, they being the sole concession holders for tourist activities in the Park. Wildnerness themselves are closely monitored by the MET but the company's attitude to tourism is both responsible and eco friendly and they are proud to be considered at this stage good guardians of these wilds. A definition of wilderness - as applicable in South Africa, who have already designated various areas of the Republic as "Wilderness Areas", these being protected in the country's legislation - is therefore perhaps relevant to us during our stay at the coast. "Such an area is defined as uninhabited, having no lasting human structures, being large enough to give a feeling of solitude, have all human activities concealed from sight or hearing and not be 'managed' in any way." Well, you sense that here you are as close as you can get in Namibia to those designations; nature is all around you, in the main unspoilt and untrammelled. You feel quite privileged to be here.

We drive on, once more hugging the seashore and head towards Rocky Point. Here we encounter a grim reminder of why this coastline is so named. In the surf lies the easily discernible wreck of the tugboat 'Sir Charles Elliott' which was carried way off course by strong currents and stranded close to the shore back in 1942. The vessel was on it's way to assist in the rescue of the British cargo liner 'The Dunedin Star' which had run aground further to the north, with over 100 people and much cargo on board. The story is wonderfully recreated in John Marsh's book 'The Skeleton Coast', a riveting tale of an astonishing rescue. In despairing efforts to save their crew mates, several members of the tugboat, which still rests here to this day, tried to swim ashore. The first mate was lost and never seen again, whilst one other crew member, Mathias Koraseb did reach the shore but then died of exhaustion. He is buried on the spot where we stand today, with a tombstone commemorating both his body and the lost first mate. They call it 'the loneliest grave in the world'. Our passage home is only interrupted by another flat tyre. Dinner tonight is taken under a giant old lead wood tree that stands proudly next to the raised decking of the lounge boma. A panoply of myriad stars in a clear African sky is almost food enough itself. And so to bed.

We begin our fourth day, after our usual wake up routine, by tracking down the Khumib River and actually leaving the concession area. Guide John wants to take us to a traditional Himba village, where the natives' lives perhaps continue closer to the format necessarily followed in days of yore than in any other part of Namibia. En route, a female Himba flags us down in the riverbed. She is wife of the chief's brother who, with her children, is living and tending their goats in an area where some showers have produced reasonable grazing, but many kilometres from the village. She begs a lift, the pungent aroma of her traditional skin covering - a mixture of red ochre and animal fat - soon filling the Defender. Her mission to get water for her dwelling, saving her a long trek by donkey. We reach the village running with one flat tyre, already the second of the day, so John - after introducing us to the village inhabitants - attends to the necessary. The centre of the village features a kraal of poles hewn locally in which the Himba dead are buried. An ancestral fire burns a few metres from the entrance. It would cause huge offence if a non tribal member were to walk between said fire and the entrance. That tract is sacred to the Himbas. Then, several women disappear into their pole based huts, which are plastered with a mixture of mud and cattle dung to keep the interiors cool and sheltered from the wind. They reappear carrying large sacks containing a huge variety of bracelets, necklaces, wood carvings and water carriers and dishes tightly woven from local vegetation. At once, the goods are displayed on mats and the area takes on the mantle of a craft market. Incongruous perhaps in these simple surroundings, but the tribes people need to make an income for themselves. One hopes that they are not too reliant on this weekly pilgrimage by our hosts. We leave for lunch at the camp, spotting a large group of Oryx in the veldt and coming across a total of seven lappet faced vultures on this single journey. During our divers travels we also had seen martial and black chested snake eagles, and also a huge spotted eagle owl. More surprisingly, near the camp we find two guys walking through the undergrowth. It turns out their vehicle has broken a drive shaft on the only local road running just outside the concession area, and one of the pair - knowing of the Skeleton Coast Camp - decided it would be best to 'trespass' into the camp area and seek help. Radio contact with the outside world would then be possible. So their long hot journey was eased by a lift. Lucky for some.

We have the opportunity to siesta briefly before our second excursion of the day. We drive out into the gravel plains and then climb up a koppie that gives us a breathtaking view of our surroundings: gravel plains, dunes, mountains - is this the best so far, a perfect snapshot of the Park, a kaleidoscope of colour, a barren but hauntingly beautiful landscape. The Skeleton Coast in one. We then indulge in solitaire, a time spent entirely on our own, each with their own thoughts, each witnessing at once the splendour and the silence. Thirty minutes well spent, refreshing the very soul.

And so to the last supper, asparagus salad, game and veggies, chocolate mousse cake and coffee. All our food delicious, with wine and cool drinks to complement same readily available. Then a surprise for even the management: the kitchen doors burst open and the full complement of staff treat us to an impromptu concert. Yolanda, Yvonne, Margaret, Isaack, Theo and Janneman - was this the Skeleton Coast Choir?

This mixture of Himba, Herero and Ovambo combined in perfect harmony, and thrilled us all. They gave us traditional songs and even indulged in theatre, portraying the very acts the songs described. During their lion hunt routine audience participation was mandatory, oh what fun.

And now, the end is near. But time still for one last escape into the great outdoors. With Land Rover we travel to near the coastline and visit a small amethyst mining operation run by a Swakopmund based enterprise who has bought a concession from the Government. Earlier in the week we had seen instances of very low key diamond prospecting concessions based much closer to the shore, although contrary to popular opinion no great tracts of diamonds in large enough quantities to warrant commercial operations have ever been found on this northern stretch of the Namib coastline. When mining for amethysts the concession holders use jack hammers to split open the geodes they uncover, revealing almost like the centre of an egg, the purple, valuable gemstones. What a wonderful place to set up your small business enterprise.

We return to camp for a last chat with Andi, a glass of Dutch courage for those who want it and say our good byes to all the staff and in particular John, our valiant guide, his biceps rippling after all those wheel changes. We won't forget John urging us to link arms and slide down the steep, steep slip face of a roaring dune. And roar it did.

But the only howl now was that of the little Cessna lifting us into the sky, and taking us back whence we came. Most of all, these memories will remain with us all for a long, long time. What else can you say about one of the last remaining wilderness areas on the planet Earth.

More Information about this trip: www.wilderness-safaris.com

Kommentar

Allgemeine Zeitung

Zu diesem Artikel wurden keine Kommentare hinterlassen